A retinal detachment is defined as the separation of the sensory retina from the retinal pigment epithelium by subretinal fluid (J.J, Kanski). This article aims to explain the risk factors, causes, symptoms and treatment of a retinal detachment.

Symptoms

As Optometrists, we all know that when a patient presents with flashes, floaters or a ‘dark curtain’ it rings alarm bells for a potential posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), retinal tear or a retinal detachment. We must dilate all patients who present with these symptoms and examine them thoroughly.

Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD)

As we age, the jelly of the eye known as the vitreous becomes more liquid like and due to this, contracts and causes what are commonly known as floaters. A small number of floaters are normal. However, if the changes in the vitreous occur suddenly, the posterior vitreous can detach from the retina causing a PVD. Although a PVD may be harmless, it is important to be aware that the vitreous may have tugged at the retina as it separated from the retina. This can potentially cause a retinal tear or even a detachment. Patients present with what they describe as a floater or lots of floaters. They may experience ‘flickering’ or ‘flashing lights’. If the patient presents with symptoms that have occurred very recently and there is no sign of a tear or detachment at this initial examination, it is advised that the patient gets re checked a few weeks later to double check that nothing has occurred. After around 6 weeks post PVD, the likelihood of any potential tear or detachment is much less.

Retinal Detachment

There are 3 main types of retinal detachment:

1.Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

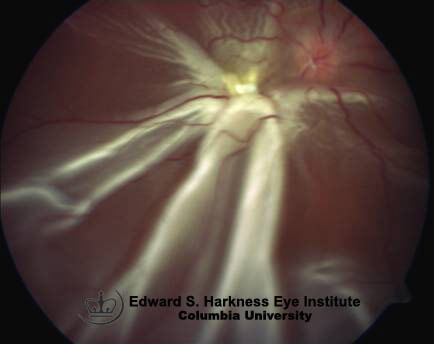

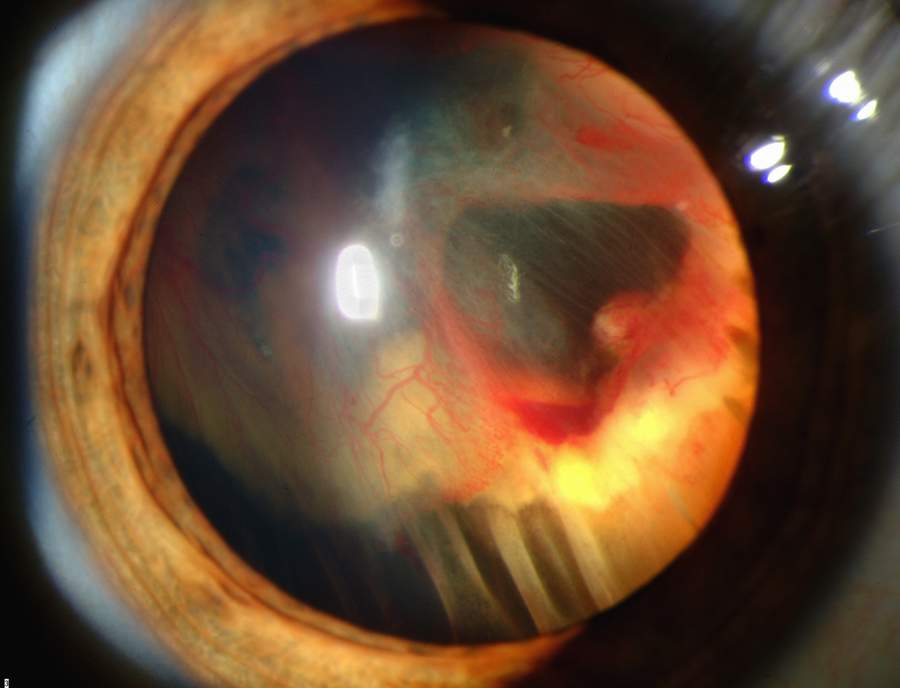

This is the most common type of detachment. The retina is fully torn allowing fluid from the vitreous to flow through and accumulate in the sub-retinal space. This in turn causes the retina to come away, taking the underlying RPE and choroid with it. Depending on the location of the tear, it can spread rapidly (wall paper effect) and involve the entire retina, causing significant vision loss and complete vision loss if the macula comes off.

2.Tractional retinal detachment

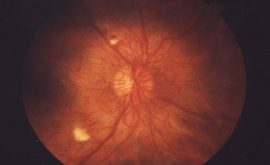

As the word traction suggests, this type of detachment occurs when the retina is pulled away. Diseases such as diabetic retinopathy commonly cause this type of detachment. For example, if new vessels have developed (neovascularisation) and then have scarred over, they may contract and tug at the retina, causing it to detach. Likewise, vitreous traction can also be a cause.

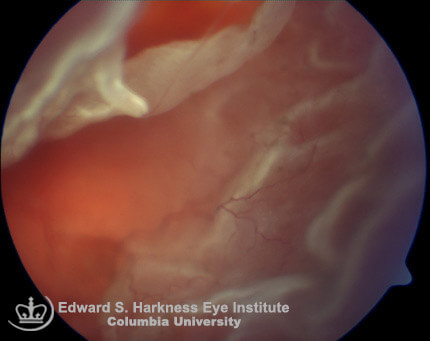

3.Exudative/Haemorrhagic retinal detachment

Although, this is not such a common cause of retinal detachment, it is important to be aware of it. It occurs due to a break down in the blood-retina barrier. Causes include congenital abnormalities, inflammatory conditions or ocular tumours which in turn damages the RPE and choroid plexus. This results in blood or fluid building up under the retina and can push the retina upwards.

Risk Factors

Posterior Vitreous Detachment

As explained above, if a patient has a PVD this increases the risk of a retinal tear or detachment.

Myopia

Over 40% of retinal detachments occur in myopes. This is due to the eye being larger than average where they also have thinner retinas, increasing the risk of tears or detachments.

Surgery

Patients who have had any form of eye surgery at at more risk of a retinal tear or detachment. As cataract surgery is becoming more and more common, we need to be aware of this risk factor.

Trauma

Any patient who has had any eye trauma is at a higher risk of a retinal tear or detachment. Impact sports such as boxing, hockey or bungee jumping increase the risk also.

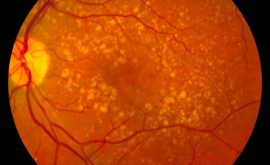

Diabetes

Diabetes can cause many complications within the body but if changes occur in the eye and are left untreated, retinal tears and detachments can result which may lead to significant vision loss. It is very important to stress the importance of diabetic control to patients.

Examination of a retinal detachment

- First step is to check for an relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) which is also known as a Marcus Gunn pupil. An RAPD suggests an extensive retinal detachment.

- Secondly, check the IOP in each eye. The IOP in the affected eye is expected to be at least 5mmHg less than the normal eye.

- Next, dilate the patient to ensure the pupil is as large as possible to get the best view.

- Using indirect Ophthalmoscopy and a superfield volk lens, examine the retina in all the cardinal positions of gaze. Also check for ‘Shafers sign’ or what is commonly known as ‘tobacco dust’. This is achieved by asking the patient to look up, down and then straight ahead again whilst you are focused on the anterior vitreous. Tobacco dust looks like little red/brown specs floating in the anterior vitreous. The movement of the patient’s eye will help to highlight them. If Shafer’s sign is seen, but no tear/detachment is visible, it is still very likely there may be a tear. Referral is still required here especially if the patient is symptomatic.

It is difficult to spot a tear and has taken me years of practise to confidently see small tears. They are not always ‘horse shoe shaped’ or oval. Sometimes they appear like a small dark area on the retina and once you pull back the slit lamp you can see the vitreous traction and then the tear behind. Retinal detachments are very obvious and they appear as a bubble/flapping area of retina that has clearly come away.

If you are unsure whether you have seen something or not it is always advisable to refer. The Ophthalmologist is able to examine the patient supine and use scleral indentation to improve fundus view. They can also do an ultrasound which is very useful for detecting tears and detachments.

Treatment

The treatment of tears and detachments vary depending on whether it is done to prevent a detachment or to fully treat a detachment.

Photocoagulation

This technique involves using a laser that lasers the affected area. This is commonly done for patients with retinal holes or small tear that hasn’t fully detached. It acts almost like glue and seals the area.

Cryotherapy

The acts in a similar way to photocoagulation with regard to sealing the lesion, but instead of a laser, a freezing cryoprobe is used. Using indirect ophthalmoscopy, the practioner views the affected area and uses the probe to indent the sclera of the eye, freezing the underlying retina. This scleral indentation is done all around the surrounding area. When the area of retina whitens it indicates the area is frozen and the treatment is complete. In cases where the lesion is behind the equator, an incision may be required rather that just indentation, to ensure the lesion can be reached. The cryoprobe is not removed until it has defrosted to prevent choroidal damage.

Scleral buckling

This is invasive surgery and involves a rubber band being literally wrapped around the eye. It works by squeezing the eye to release tension and enable the retina to touch the retinal pigment epithelium. This allows the lesion to heal. It is a good method for patients who have lesions around the equator of the eye due to the ability to ‘buckle’ the area freely. However, for posterior lesions this is not the treatment of choice.

Pneumatic retinoxpexy

Compared to scleral buckling, this is a less invasive method to seal a retinal break. This is commonly used for less severe tears or breaks and although not as successful as scleral buckling, it still has a relatively good outcome. It involves an expanding gas bubble or silicone oil being injected into the vitreous of the eye. This then pushes the retina back into place. If gas is inserted, the patient must lie flat for several weeks in order to keep the bubble in place. This is very uncomfortable for the patient but the alternative is the oil bubble, which must be removed again once the lesion has healed. The gas bubble reabsorbs back into the body eventually.

Victrectomy

This is done when a patient has a severe retinal detachment with possibly a combination of other problems such as vitreous haemorrhages or neovascularisation. The vitreous is removed and then there is access to the retina. It can then be manually sat back down and any other causes of traction removed.